The story of the Antigua finish begins less with a grand design vision and more with a practical workaround. According to Fender lore and secondary sources, Antigua was originally conceived in the late 1960s as a way to mask wood flaws or finishing defects — particularly on Fender’s hollow or semi‑hollow lines, notably the Coronado II.

The Coronado line (introduced mid‑1960s) reportedly encountered issues where bodies or laminates had scorch marks, glue marks, or blotches that didn’t cleanly finish. Rather than reject the parts, Fender experimented with a layered spray finish that moved from a dark (grey / charcoal) outer “halo” or mist into a creamy, off‑white center. This would help conceal imperfections while giving a distinctive “bursting into white” effect.

Over time, what began as a utilitarian “cover up” evolved into a somewhat idiosyncratic aesthetic. As one blogger puts it, Fender used Antigua to “cover manufacturing flaws in its Coronado II line.”

In short: Antigua was never meant to be a “classic finish” in the way Sunburst or Olympic White were; it was an invention born of necessity.

Spread and “cult unpopularity” during the ’70s and ’80s

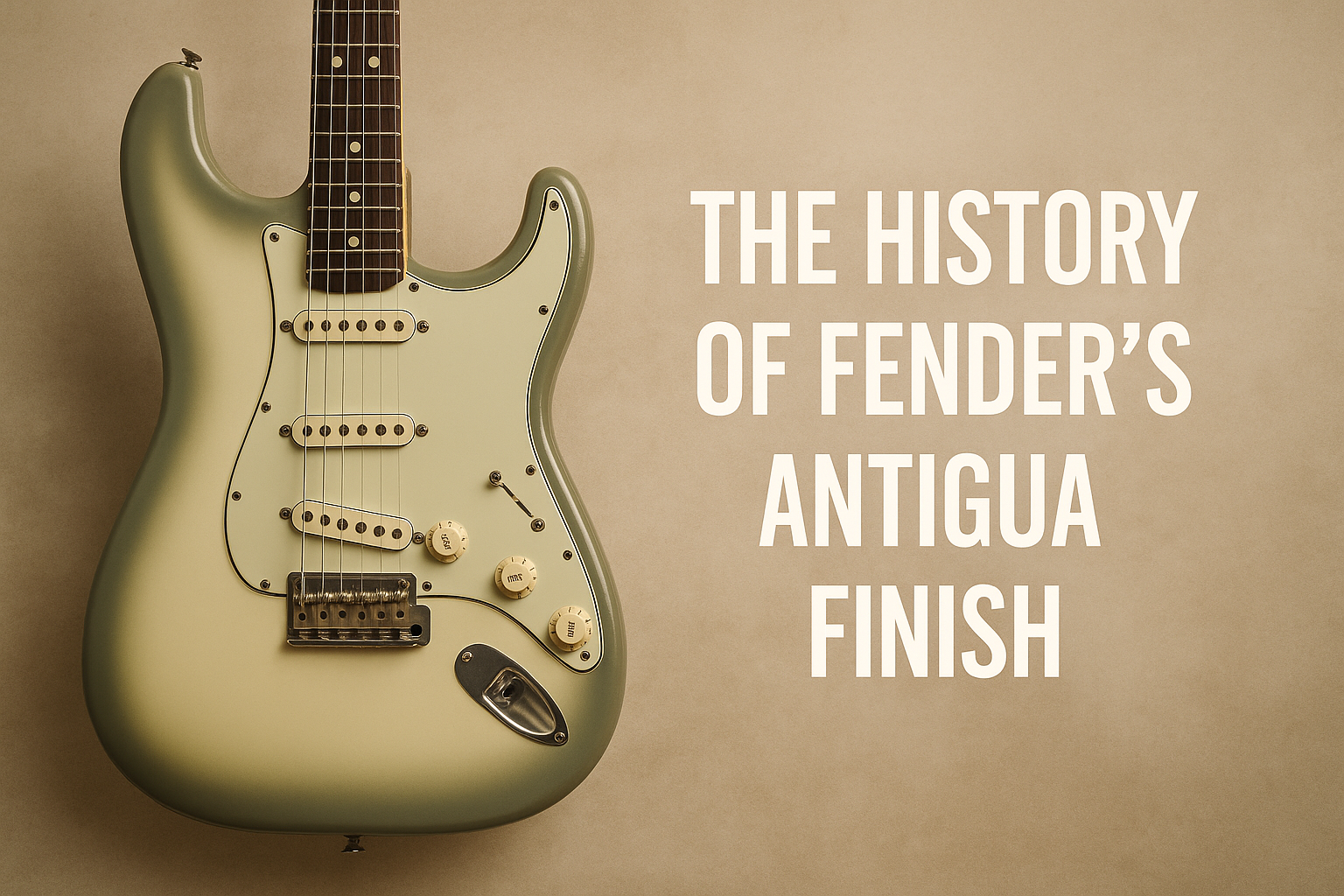

Despite its humble origins, during the 1970s Fender extended the Antigua finish into several of its solid‑body models — particularly the Stratocaster, Telecaster, and basses.

However, the finish never caught public favour. Many players derided it as ugly or garish; some dismissed it as a “mistake.” Some quotes from vintage guitar forums illustrate this:

“This finish is wearing off … the pickguard was beginning to crack … I resprayed it.”

“They were available only for a very short time … Antigua finish Fenders are really hard to find.”

“People sort of started to take notice … they actually sold ok (in Japan, anyway).”

Because of its unpopularity, many Antigua‑finished guitars were either ignored, refinished, or scrapped. It faded into a sort of cult curiosity — a finish that most players preferred to cover up rather than embrace.

One interesting note: some believe that in the Stratocaster/Telecaster lines, Antigua was offered only briefly (perhaps around 1978) on non‑Coronado models — though the precise span and volume is debated among collectors.

Over the years, Antigua became a punchline among guitar aficionados — sometimes called “spewburst” for its odd green/gray/cream halo — but it also developed a small fan base intrigued by its oddity and rarity.

Why it divides opinion

Why does Antigua provoke such strong reactions — negative or otherwise? Here are a few reasons:

-

Aesthetic boldness: It’s not a safe or subtle finish. The stark outer halo and the fade into a pale center create a dramatic effect that some see as too bold or even ugly. Some players feel it clashes with wood grain or instrument shapes more than traditional finishes do.

-

Color stability and wear: Over time, Antigua finishes may age unevenly, fade, or crack, revealing undercoats (often black) in places. Some note that worn edges expose the underlying layers, turning portions of the guitar darker.

-

Associations with CBS era / cost cutting: Because Antigua is tied to a period in Fender’s history known for cost-saving measures and quality debates, the finish carries some of that baggage.

-

Narrow usage and rarity: Because it was never broadly popular, finding a clean original Antigua is rare, and many guitars that do exist have damage or wear, making judgement harder.

Yet for some, those same traits are compelling: it’s distinctive, polarising, and enigmatic.

Revival: reissues and modern takes

In more recent years, Fender (and its sub‑brands) have revisited Antigua as a kind of retro curiosity or limited edition. This revival taps into vintage appeal, cult status, and a renewed appetite for wilder or more individual finishes.

-

In its 70th Anniversary Stratocaster line, Fender reintroduced the Antigua finish, complete with hand‑painted matching pickguard.

-

Fender and Squier have also used Antigua in limited runs or special models (e.g. Squier Classic Vibe ’70s Antigua Burst) to acknowledge the finish’s place in the Fender lore.

-

Among collectors and boutique builders, the finish has gained some cachet: owning a clean Antigua is a point of pride, and some builders/relighters use it as a relic or “what-if” aesthetic.

That said, Antigua remains a niche finish rather than a mainstream one. Its revival tends to be for limited or anniversary models, not for regular catalog colors.

Examples & collectibility

Because of its rarity, surviving original Antigua guitars are collectible. A few example models include:

-

1978 Stratocaster (hardtail) in Antigua — cited by dealers as very rare and sought after.

-

2003 Telecaster “Antigua” — an example of Fender applying the finish in later years.

-

2012 MIM Antigua Stratocaster FSR — a limited factory special run showing the finish’s occasional comeback.

Collectors prize examples with original matching pickguards, minimal refinish, and uniform fading or patina rather than patchy wear.

One collector forum also argues that the pickguard itself on many Antigua guitars was painted in layers (Antigua over darker undercoats), so that as the finish wears you see “rings” of colour — a kind of “history in paint.”

What we can learn from Antigua

The saga of the Antigua finish offers several lessons (or at least interesting insights) into guitar design, branding, and collector culture:

-

Aesthetic accidents can become legends — what begins as a workaround or stopgap can, over time, assume mythic status.

-

Divisiveness can fuel cult appeal — polarising finishes often stay under the radar, but that very obscurity can increase their allure among niche fans.

-

The virtue of rarity — because so few remain in original condition, every surviving Antigua is disproportionately valuable to enthusiasts.

-

Brand willingness to revisit oddities — Fender’s occasional reissues show a willingness to lean into its quirky back catalog, not just its “safe” relic lines.

-

Finish matters — the finish is not just cosmetic; it interacts with wear, fading, aging, play patterns — meaning each Antigua is unique.