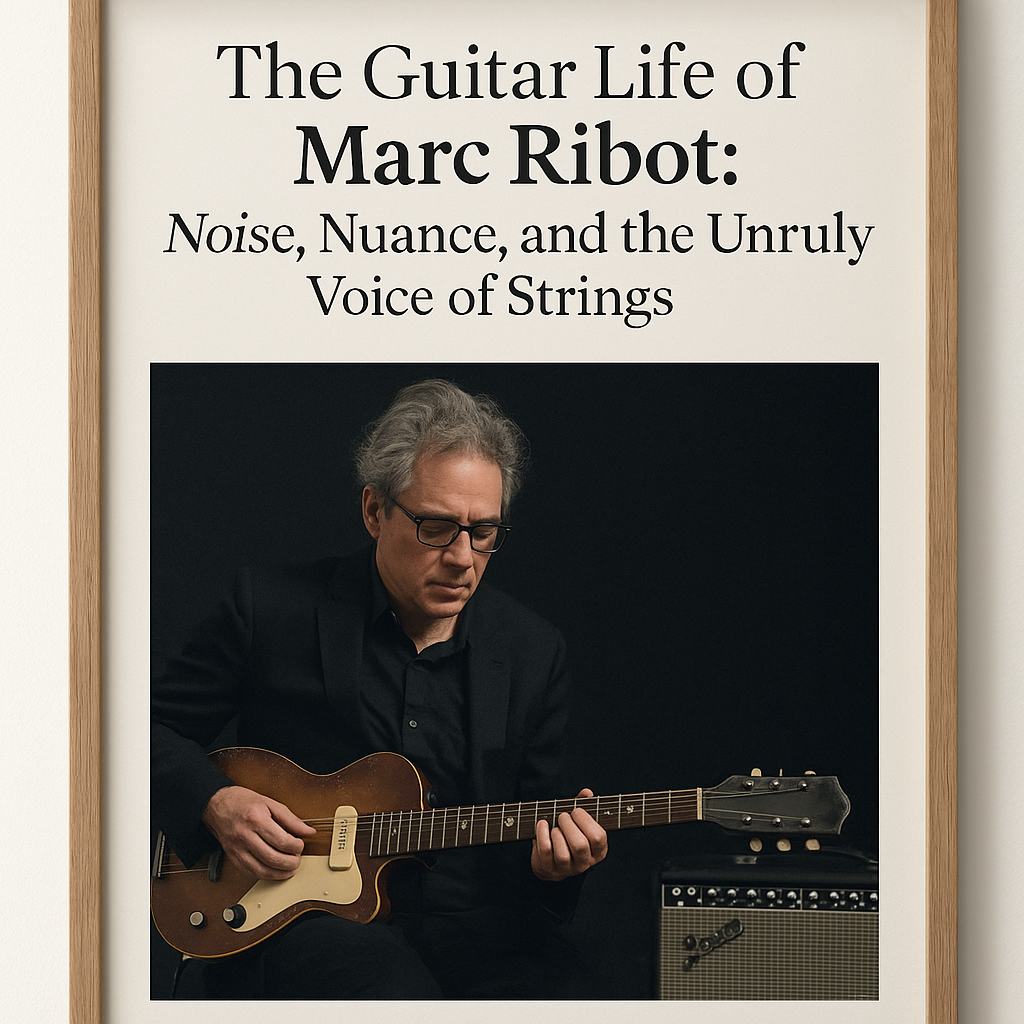

Marc Ribot is a guitarist in the loosest, and most liberating, sense of the term. Across four decades of recordings, collaborations, and dissonant detours, he has shown that the instrument can be a knife, a whisper, a weapon, a ghost — and sometimes, simply a rhythm machine in a Cuban dance band. His guitar history is not a catalog of technical mastery, but a chronicle of rebellion against expectations.

Born in 1954 in Newark, New Jersey, Ribot first encountered the guitar as a teenager in garage bands, covering the R&B, rock, and soul records that blasted from car radios and basement stereos. But it was his classical training with Haitian guitarist and composer Frantz Casseus that left a lasting imprint. Under Casseus’ guidance, Ribot studied the possibilities of melody and texture, not in pursuit of conservatory perfection, but to learn how music could carry culture, memory, and pain.

When he moved to New York in the late 1970s, Ribot found himself at the crosswinds of chaos and experimentation. He worked as a sideman in soul and R&B outfits, backing legends like Wilson Pickett, Chuck Berry, and Carla Thomas. Yet even then, the avant-garde beckoned. He soon joined The Lounge Lizards, John Lurie’s downtown jazz-punk collective, and began forging his reputation as a player who prized attitude over ornament.

Gear and Grit: Guitars as Extensions of Personality

Unlike many guitarists who chase tonal purity or vintage pedigree, Ribot often chooses instruments that sound broken, raw, or ill-suited to the task at hand. His gear, like his music, resists easy classification.

One of his favoured instruments over the years has been the Harmony H44 Stratotone — a short-scale, single-pickup solid-body built in the 1950s. In Ribot’s hands, the H44 is not a relic but a conduit for guttural, metallic tones. Its thick DeArmond pickup delivers a woolly, barking midrange that can seem as much amplifier as guitar. He has called it a “punk guitar,” but used it on delicate Latin ballads and jazz explorations alike.

Another key guitar in Ribot’s arsenal is a 1963 Fender Jaguar, which featured prominently on his Rootless Cosmopolitans recordings and later solo work. With its short scale, bright pickups, and floating tremolo, the Jaguar allows for a palette of washed-out textures and surf-like shimmer — but Ribot often turns it inside out, coaxing from it wild harmonic squeals and percussive thunks rather than clean chords.

He has also been seen with:

-

A 1950s Harmony Rocket (for raw electric blues and Cuban son),

-

A Gibson ES-125T hollowbody (favoured for jazzier tones and feedback manipulation),

-

A Fender Stratocaster (used occasionally for sessions and sideman gigs),

-

And an unnamed nylon-string classical guitar, likely a Thomas Humphrey Millennium model, used on his album Plays Solo Guitar Works of Frantz Casseus.

In terms of amplification, Ribot often gravitates toward small combo amps that break up easily. He’s used:

-

A 1960s Fender Deluxe Reverb, for its warm overdrive and responsiveness to touch,

-

A Silvertone 1482 tube amp,

-

Occasionally Fender Princeton Reverbs or Ampeg Jets, depending on the desired grit and growl.

Effects are minimal — Ribot is not a pedalboard obsessive. He has used MXR distortion, occasional delay or reverb pedals, and at times a volume pedal for dynamic swells. But for the most part, his sound is in his fingers, his timing, and his instincts.

Notes That Bleed and Bite

Ribot’s technique is, by his own admission, unconventional. A left-hander who plays right-handed, he has often said that his physical relationship to the instrument feels “awkward” — but that awkwardness has become part of his voice. He bends notes too far. He digs in too hard. He lets chords ring out with unresolved harmonics or cuts them off like a slammed door.

His playing is filled with intentioned imperfection. There’s a deliberate use of buzz, scrape, silence, and overdriven feedback. He has compared the guitar to a human voice — not in the lyrical, melodic sense, but as a conduit for rage, sadness, and irony.

On albums like Don’t Blame Me (1995), Ribot interprets jazz standards as if decoding a forgotten language. On The Prosthetic Cubans (1998), he channels Arsenio Rodríguez and 1940s Cuban son through his own jagged sensibility, playing tumbao riffs with the urgency of a punk band. And on Silent Movies (2010), he creates haunting soundscapes that feel like solitary dreams.

Collaborator and Chameleon

Beyond his own projects, Ribot has lent his voice to a staggering range of artists:

-

Tom Waits, on landmark albums like Rain Dogs and Real Gone, where Ribot’s sharp, metallic tones became the sonic glue between junkyard percussion and dark balladry.

-

Elvis Costello, on Spike and Mighty Like a Rose,

-

John Zorn, in multiple avant-garde and klezmer-fusion projects,

-

Robert Plant & Alison Krauss, The Black Keys, Neko Case, and many more.

In every context, his guitar remains unmistakable: not always clean, never complacent, and often just a little bit dangerous.

The Voice Behind the Strings

In 2021, Ribot published Unstrung: Rants and Stories of a Noise Guitarist, a book of essays and reflections that reads like a manifesto of sonic resistance. In it, he argues against perfectionism and embraces the flawed, the improvised, the contingent. His approach to the guitar — and to music itself — is as a means of protest, expression, and communication, even when the message is messy.

Marc Ribot’s guitar history is not about models and specs, though those are part of the story. It’s about why a jagged note can cut deeper than a flurry of clean ones. It’s about choosing a guitar that misbehaves and making it speak. And it’s about never, ever playing it safe.